Aramark Chefs were joined by representatives from the US Dry Pea and Pulse Council for an introduction session to incorporate Pulses into more of our recipes. Tim McGreevy, CEO at USA Dry Pea and Lentil Council, Jessie Hunter, and Alexei Rudolf are here to share knowledge and insights about these powerful plant forward ingredients, and Christine Farkas and our own Scott Zahren will talk and let us taste samples from their experiences cooking with all types of pulses during the Pulses of Change workshop earlier in April.

Dry peas, lentils, and chickpeas— known as pulse or legume crops—are among the world’s most ancient commodities. Archeologists have discovered peas in caves in what is present day Thailand that date back more than 11,000 years. The royal Egyptian tombs contained lentils, which were meant to sustain the dead on their journey to the afterlife. In the Christian Bible, Esau sold his birthright for a pottage of lentils. And, in Italy, the names for peas (Pisum sp.), lentils (Lens culinaris), and chickpeas (Cicer arietinum) found their way into the names of the prominent Roman families of Piso, Lentulus, and Cicero. According to Italian writer and Academic Umberto Eco, it may even be true that peas, beans, and lentils actually saved Western Civilization during the Early Middle Ages (476 to 1000 AD). It is well documented that the introduction of pulses into crop rotation practices resulted not only in increased farm productivity, but also in improved protein content and a more diverse and nutritional diet for the populace. The development is credited with saving generations of people from malnutrition and helping facilitate the repopulation of Europe after the Black Plague pandemic of the late 1340s.

Tim McGreevy, CEO at USA Dry Pea and Lentil Council

Perhaps in recognition of legumes’ extraordinary qualities, many cultures have developed a range of traditions in which the eating of peas and lentils figure prominently. Among the most notable is No Ruz, the New Year’s celebration in Iran. During this 13-day celebration, every house maintains a table known as the “seven S’s,” which includes seven symbolic objects beginning with the letter S. Germinating lentil seeds, known as sabzi, hold the place of honor in the center of the table to symbolize renewal and rebirth. For hundreds of years, the people of northern Italy have enjoyed their own New Year’s tradition called Capo d’Anno (literally “head of the year”) in which lentils, symbolizing coins, are eaten to ensure good fortune for the year ahead. Consuming these “coins” is thought to make wealth and prosperity part of one’s blood and being. Eating lentils, rather than more exotic or expensive foods, is also considered an act of humility to both heaven and society, and a means for averting the sin of pride.

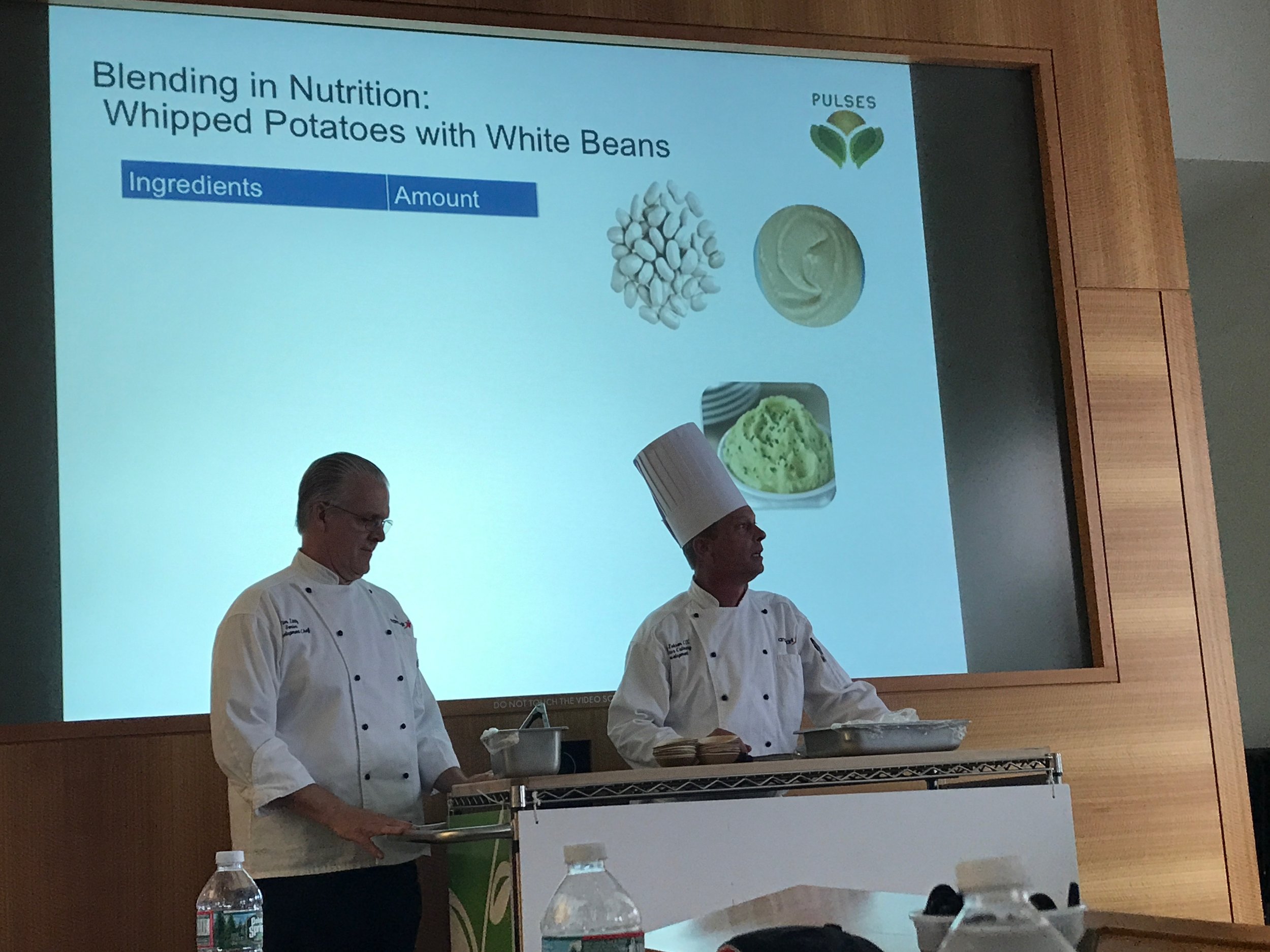

Chef Tim Zintz and Chef Scott Zahren culinary demo on Whipped Potato & White Bean

Over time, the United States has seen much of its own rich tradition of eating legumes replaced by a preference for fast food and microwavable meals. Fortunately, Americans are starting to rediscover these overlooked ingredients. Nutritionists have, for example, begun pointing to the legume rich diets of the Mediterranean as one possible route to improved health. The media, meanwhile, is increasingly touting the benefits of the nutritional attributes and phytochemicals found in legumes. Recent research shows that the antioxidants, flavonoids, plant estrogens, vitamins, minerals, protein, and fiber in legumes can help prevent, and may even contribute to, the reversal of many major chronic diseases. Add these health benefits to their delicious flavor and incredible culinary versatility and it is little wonder that Americans are once again finding a place for peas, lentils, and chickpeas in their diets and on their dining

room tables.

Chefs jumped in the kitchen to create recipes. Here are some of the creations: